Abraham Lincoln and Union Pacific

Uniting the States of America

First north to south. Then east to west.

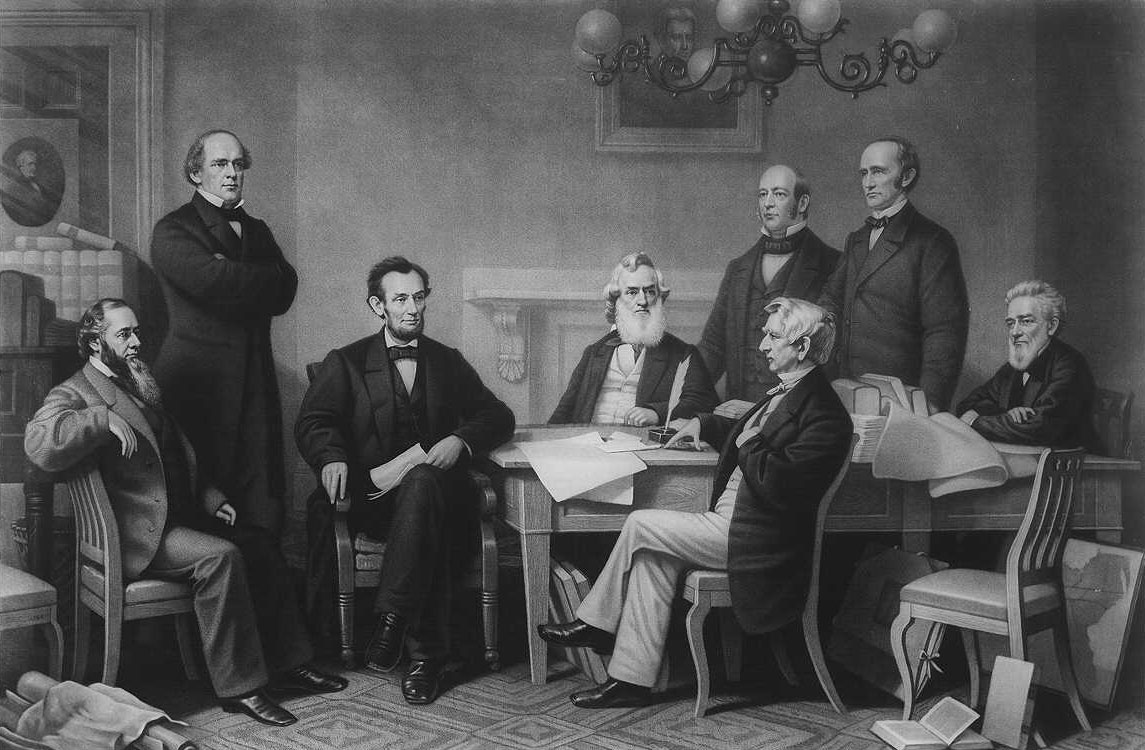

Union Pacific is proud to celebrate the legacy of Abraham Lincoln – who set the transcontinental railroad in motion and brought our railroad to life.

When your company's first task is to unite a continent – when you can count Abraham Lincoln himself as a founding father – it gives you such purpose. Such intrinsic pride.

At Union Pacific, we credit much of our success to our unique history, a history that began with Lincoln and the nation's first transcontinental railroad.

The right time, the right man.

Abraham Lincoln will forever be remembered as the man who held our nation together during its most uncertain hour. No other president has fought so hard – or sacrificed more – for our union.

But Lincoln's legacy as “the great uniter” reaches far beyond the resolution of the Civil War.

At the height of that war, with unity so much on his mind, President Lincoln sought a way to connect and secure the great expanse of our nation, to unite it entirely, from sea to shining sea.

A transcontinental railroad.

This wasn't a new idea. Visionaries first began talking about a route to the Pacific in the 1830s. Indeed, by the time Lincoln took office in 1861, many Americans believed that expanding the railroad was absolutely necessary.

Lincoln and the Railroad

Congress had tried to make it happen and failed. There was so much to argue about … Who would pay for it, and who would build it? And where would it begin and end?

Many leaders felt that the time for such a massive undertaking was not in the middle of an expensive Civil War. But the president was determined. At the same convention where Lincoln was nominated, the Republicans pledged to stop the spread of slavery, to establish daily mail service and to build a transcontinental railroad.

In Lincoln's mind, the railroad was part of the Civil War effort.

The new line would support communities and military outposts on the frontier. It would give settlers safe and dependable passage west. And most importantly, it would tie new states California and Oregon to the rest of the country.

These states were rich with natural resources and trade potential, and their place on the flag was far from secure. Little more than a decade had passed since Oregon was claimed by Great Britain and California was part of Mexico. Even after becoming a state, California had its own secessionist movement.

A transcontinental railroad, Lincoln hoped, would bring the entire nation closer together – would make Americans across the continent feel like one people.

On July 1, 1862, after decades of debate and disagreement on the matter, Lincoln brought the transcontinental railroad to life with a stroke of his pen.

And with that same stroke, he created Union Pacific.

On July 1, 1862, after decades of debate and disagreement on the matter, Lincoln brought the transcontinental railroad to life with a stroke of his pen.

The Pacific Railway Act of 1862 gave the work of building the railroad to two companies: Central Pacific, an existing California railroad, and a new railroad chartered by the Act itself – Union Pacific.

Central Pacific would start at the Pacific and head east, and Union Pacific would start in the middle of the country, the beginning of the frontier, and head west. What path Union Pacific should take was a matter of much contention. Lawmakers already realized the impact the railroad could have on local economies and wanted the business for their own states.

Lincoln and Union Pacific

Even before he became president, Lincoln, a railroad attorney, had an avid interest in the Pacific route. On a visit to Iowa in 1859, he met with Grenville Dodge, who would one day become Union Pacific's chief engineer.

Dodge later wrote in his “Personal Recollections of Lincoln”:

"Mr. Lincoln sat down beside me and, by his kindly ways, soon drew from me all I knew of the country west and the results of my reconnaissances. As the saying is, he completely ‘shelled my woods,' getting all the secrets that were later to go to my employers."

Lincoln remembered Dodge's expertise and summoned the engineer to Washington in 1863 to discuss a starting point for Union Pacific. Dodge was adamant: the railroad must follow the Platte Valley and begin at Omaha-Council Bluffs.

On November 17, two days before the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln issued an executive order setting the railroad's eastern terminus exactly where Dodge had advised.

Union Pacific broke ground in Omaha in December 1863. Unfortunately, due to many delays, the first rails wouldn't be laid until July 1865, three months after the president's death.

President Lincoln would never see the completion of the transcontinental railroad, but perhaps he foresaw how it would change us. How it would draw Americans together – by trade, by travel and even by thought.

Days after the driving of the Golden Spike, the first passenger service began. Travel between San Francisco and New York City – once a months-long, perilous journey – now took less than a week.

A Nation Transformed

For settlers along the railroad's path, the tracks were a lifeline. More than 7,000 cities and towns west of the Missouri began as Union Pacific depots and water stops.

Trade flourished between the two coasts and beyond; the first freight train to head east from California carried Japanese tea. By 1880, about $50 million worth of freight traveled the rails each year.

But none of these changes were as dramatic as the railroad's effect on American culture. The transcontinental railroad captured the country's imagination. Driving that Golden Spike was as exciting as putting a man on the moon. And once the railroad was complete, it changed the way Americans thought about themselves and each other.

Trains carried ideas as efficiently as freight. With books, newspapers and people criss-crossing the continent daily, Americans in every corner of the country could participate in the same national conversation.

Test your knowledge of Honest Abe by taking our quiz!