On a warm and sunny Saturday in late July, the Next Level Sports Complex in Garden Grove, California, is humming with the sound of basketballs – dozens and dozens of them – bouncing off the polished hardwood floors. There’s a tournament here today, and teams of young boys and girls from all over the state have come to compete in this weekend’s event.

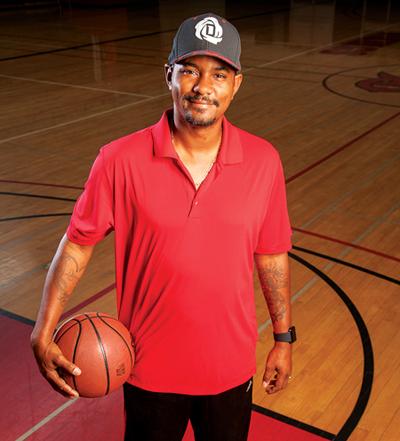

Among them, Trinity basketball, a team of 7- to 11-year-olds coached by Darrell Henry, a Union Pacific machinist at the Dolores Locomotive Shop in Carson, California. After a series of stretches and warm-ups, Henry calls the team over. They quickly assemble around him and quiet down as he goes over the plays for today’s game. The kids are attentive and respectful. When Henry finishes a sentence, they respond loudly and in unison “Yes, coach.”

Henry has been coaching basketball as a hobby for several years, but it’s the after-school program he recently started that truly speaks to where his heart and passion lie. For eight weeks this spring at Purche Elementary School in nearby Gardena, Henry combined basketball drills with financial education. His goal is to teach kindergarten through 5th grade kids, many from single-family homes, what he never had growing up: a respect for money, and enough knowledge to understand how to manage it correctly.

“A lot of these kids say they want to be basketball players because they see these rich athletes and they want to grow up and have all the cars and houses that these guys have,” says Henry, 43, a tall, lean man who looks like he could still easily sink a three-point shot. “I tell them to do research on the athletes that had it all and then lost it. That happened because they never bothered to take the time to learn how to manage their money.” Henry aims to be that teacher.

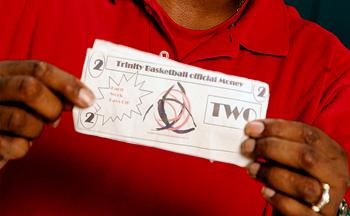

Henry with two Trinity dollars.

Toward the end of each practice, he sets aside time to teach the kids about checking and savings accounts, the basics of interest, and how to write out a check. Students are given paper “Trinity money” for taking part in challenges, and they are awarded prizes and trophies for making smart decisions about spending and saving. In fact, some of the kids can easily recite the financial terms and definitions he taught them. Henry says he’ll teach the program again at Purche in September, and is in talks with another nearby school district to offer it there as well.

The idea the program was always in the back of his mind, Henry says. The final push came several years ago after an eye-opening visit to the grocery store with this then-8-year-old son, Darrell Jr. (In addition to his son, Henry and his wife of 24 years, Maisha, have two daughters, Dionna, 20, and Dominique, 13.) “I had $40 cash with me, and when we got to the register my son wanted bubble gum and some toys and that would have put me over $40,” he recalls. “I explained to him that I didn’t have enough money for those extras and he said, ‘Daddy, just use your card.’” It was then that Henry realized there were probably lots of young children like his son. “These kids see their parents use an ATM or a debit card in a store, but have no idea that there has to be money in the bank to begin with,” he says. “So I figured I could teach them now, so that they would be better prepared about money when they grow up.”

An Early Life of Loss

Henry could have used someone like him as a young boy growing up in a rough neighborhood in Compton, California. His father died of a drug overdose when he was a month old. His mother struggled with her own substance abuse, and when she spent all their rent money, Henry and his brothers and sisters had to live with their paternal grandparents. “They were kind of old, so they really couldn’t take care of us that well,” he says. Without any consistent parental guidance, Henry’s early teen years were shaped by neighborhood friends who were often running afoul of the law. He got into his own share of legal trouble, he admits, but by the time he was 16, he was tired of the life he was living. “I wanted to make something of myself and be better than what I saw around me,” Henry says.

He showed up at Burger King every day for 30 days, until the manager finally relented and gave him a job. Instead of hanging out in the neighborhood, Henry turned to sports in school, playing baseball, and making friends with the jocks. When high school was over, he enlisted in the Navy and was stationed on the USS Peleliu. Over the next eight years, he did two tours of duty, including time in Kuwait and the Persian Gulf. In 1999, he joined Union Pacific as a machinist.

Finding the Good

Henry says one of his biggest challenges with the afterschool basketball program was figuring out how to channel all that youthful energy and attitude into something positive. One boy, who he nicknamed “Wreck-It Ralph,” after the Disney movie character, was continually bullying other students and causing problems. So Henry tried a different approach. “I put him in charge of leading the stretches and warm-ups for the younger kindergarten kids and he just loved it – and they loved him,” Henry recalls. He later told the boy’s mom, “You have a leader here, and you have to tell him that and cultivate that in him.”

Darrell Henry has been coaching basketball as a hobby for several years, but it’s the after-school program he recently started that truly speaks to where his heart and passion lie.

That kind of positive, strong male influence is appreciated among the parents, especially single moms like Juanita. Her son AJ plays for Henry, and when she lost her husband last August, Henry and his family were there for her. “Darrell spends time with AJ and really helped us through a very difficult time,” she says. “He gives his heart to the program and to these kids.”

As game time nears, Henry has one final huddle with this team. The boys are pumped as they gather their backpacks and head over to the court to face their opponents. Before Henry leaves, we have one more question. What does he get out of all this? What’s the reward for teaching these kids about how to be better with money? He stops a moment to think, and then the answer comes. It doesn’t take long to realize that he’s probably speaking as much about them as he is about his younger self.

“I love bringing out the best in kids who don’t have someone to bring it out for them. Taking a kid who has never been told he was great, was never really loved, never told he was good at anything,” he says. “I want them to hear from someone that they’re a good person, that they’re smart. And I want these parents to hear from me, and in front of their kid, that I think these kids have worth.”

It’s a message Henry sorely missed out on in his own early life. He’s doing all he can to make sure history doesn’t repeat itself.