Done. A single word telegraphed around the nation triggered champagne toasts, cannon booms from coast to coast, fireworks and the ringing of The Liberty Bell in Philadelphia. It was a celebration of the country’s greatest achievement – completion of the transcontinental railroad – and the joining of East and West. Reporters, politicians and workers heralded the completion as the Eighth Wonder of the World on May 10, 1869.

Subscribe to Inside Track

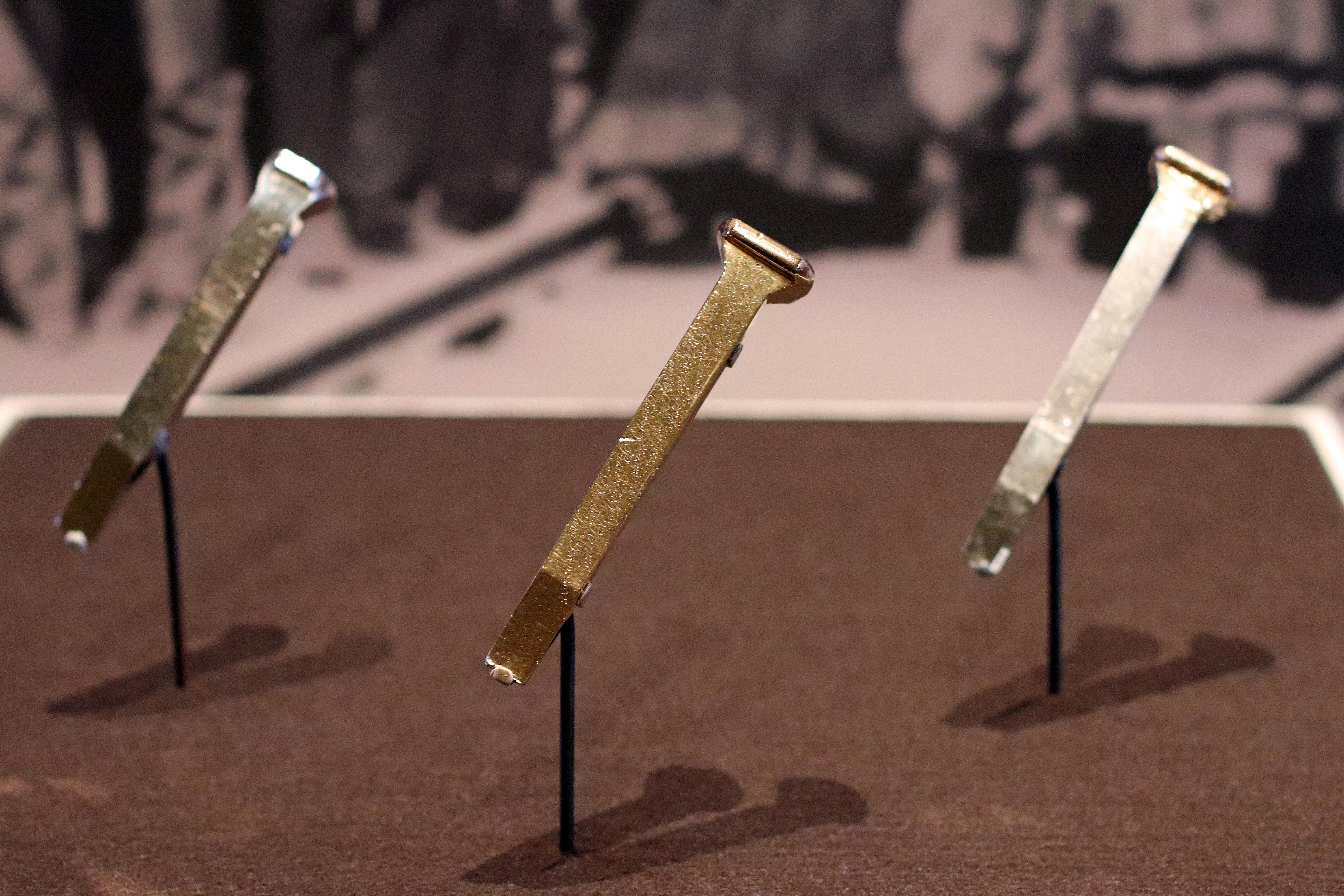

For the first time since that windy day at Promontory Summit, three of the original four spikes driven to honor the transcontinental railroad's completion are being reunited in Omaha, Nebraska, a few miles from mile zero, where Union Pacific laid its first rail near the Missouri River, as ordered by President Abraham Lincoln. The spikes will sparkle as the centerpiece of a new traveling exhibition, The Race to Promontory: The Transcontinental Railroad and the American West, opening Oct. 6, at Joslyn Art Museum.

“This is an once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see railroading’s crown jewels reunited,” said Patricia LaBounty, Union Pacific Museum curator.

President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act of 1862, authorizing Central Pacific Railroad of California, chartered in 1861, to build a line east from Sacramento. At the same time, the act chartered the Union Pacific Railroad Company to build west from the Missouri River. The original legislation granted each railroad 6,400 acres and up to $48,000 in government bonds for each mile completed, igniting The Great Race to Promontory.

The Original Golden Spike and its Promontory Summit Companions

For a century and a half, the Golden Spike has symbolized one of the most audacious and significant undertakings in American history – completion of the world's first transcontinental railroad. Schoolchildren learn about the famous spike, but few know about its companions at Promontory Summit or this tale's unexpected twist. Read more.

More than 20,000 men worked through harsh winters and blistering summers, laying 1,776 track miles. Completion provided something new for Americans – convenience. Within days, the country was transformed. Travel from New York to San Francisco was reduced from six months to 10 days, and at a fraction of the cost.

For communities created along the route, economic opportunity and prosperity were taking root. Agricultural products transported east from California changed what filled dinner tables, and communication flowed quickly and reliably on mail cars and across telegraph lines. The railroad changed the concept of a “frontier.”

To celebrate the engineering marvel, the idea of driving home a golden spike at Promontory Summit appealed to the romantic spirit embraced by many 19th-century Americans. David Hewes, a well-known San Francisco contractor, was no exception. He ordered a spike cast of 17.6-carat gold alloyed with copper polished and engraved with the words “The Last Spike” as a gift for Central Pacific President Leland Stanford.

News of the golden spike spread quickly, and others scrambled to get a piece of the action. Four ceremonial spikes were present at Promontory for Stanford and Union Pacific Vice President Thomas C. Durant to place into a laurel wood tie – the Golden Spike; a silver spike presented by the newly-formed State of Nevada; a blended spike of iron, gold and silver provided by the Territory of Arizona; and a second, lower-quality golden spike presented by Frederick Marriott, proprietor of a San Francisco-based newspaper.

“The spikes were truly a grassroots ‘thank you,'” LaBounty said. “They were not created by the railroads to celebrate their own achievement, but gifted by the communities, and territorial and state governments in recognition of the perceived societal benefit brought by the railroad.”

Registrar Dolores Kincaid from Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, places The Golden Spike in the exhibition.

It was the first and last time all four spikes would be together. One was lost to history, while the others found separate homes. The Golden Spike and silver spike are part of the collection at the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University. The “Arizona Spike” belongs to the Museum of the City of New York, but is on long-term loan to the Union Pacific Museum in Council Bluffs, Iowa.

While impressive in their own right, the spikes are only part of the exhibition, which celebrates the railroad’s construction through the photographs and stereographs of Andrew Russell and Alfred Hart. Their work, drawn exclusively from Union Pacific’s collection, visually recreates the meeting of the rails.

A modern-day stereograph experience is available at the Joslyn Art Museum using facsimile viewers.

“It’s fascinating that both railroads chose photographers to document their journey, rather than a painter or print maker,” said Joslyn Art Museum’s Chief Curator and Holland Curator of American Western Art Toby Jurovics. “If you think about it, the most modern invention in transportation was being documented by the most modern artistic medium – photography.”

Central Pacific attorney E.B. Crocker paid Alfred Hart $150 for 32 stereograph negatives showing the railroad’s early progress in California in January 1866. Prints made from these initial negatives were used in New York City to attract financial support. The message was one of progress, and it was easy for a viewer to experience first-hand looking through a hand-held stereo lens that created a three-dimensional view of the world.

“Viewing stereographs is a more intimate experience than looking at prints in an album or framed on a wall,” Jurovics said. “Exhibition visitors will see Hart’s stereographs in facsimile viewers that replicate the 19th-century experience of seeing these fascinating images and more than 100 additional stereographs displayed in wall-mounted cases.”

Hart made more than 500 negatives, and Crocker selected 364 to represent Central Pacific’s railroad construction, documenting the transition from wilderness, to industry and settlement. A Union Pacific executive saw Hart’s work and his competitive spirit led to Andrew Russell, a painter who enlisted in the Civil War and was trained as a photographer working with the Army Railroad. Russell understood how to operate a darkroom wagon in the field and transport his fragile equipment on the rails. He joined The Great Race in 1868, capturing Union Pacific’s journey west.

“There were few opportunities for landscape photographers at this time,” Jurovics said. “If Russell had not had the good fortune of working for Union Pacific, it is unlikely we would have this forthright and direct – and sometimes elegant and lyrical – record of the American West.”

Unlike Hart’s work, most of Russell’s photographs were Imperial plate albumen prints, measuring roughly 9x12 inches. The wet-plate process used resulted in crisp, detailed images capable of remarkable subtlety.

Hart and Russell both worked to capture the railroads’ progress and the beautiful, rugged terrain.

Russell and Hart were both present at Promontory Summit but it was Russell who took what would become the day’s most famous photo titled "East and West Shaking Hands at Laying Last Rail." The moment captured a feat as celebrated as the first moon landing, exactly one century later in 1969.

“Art works in a unique way,” Jurovics said. “It’s more than standing in front of a photograph or painting in a gallery, it can transform how you think about place and its history.”

The Race to Promontory: The Transcontinental Railroad and the American West exhibition is on view at Joslyn Art Museum Oct. 6 though Jan. 6, 2019. At the conclusion, the spikes will return to their respective homes; however, the photograph collection will move to the Utah Museum of Fine Arts Feb. 1 through May 26, 2019, and then the Crocker Art Museum June 23 through Sept. 29, 2019.

For the first time in nearly 150 years, the three original, ceremonial railroad spikes presented during the festivities at Promontory Summit on May 10, 1869, are reunited at Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska.