Meet Matt Wallace. An avid rock climber and a decent skier, Wallace graduated from Temple University last May with a bachelor's degree in journalism. The 25-year-old go-getter is optimistic about an upcoming job interview. Later this month he's looking forward to moving out of his parents' house to live with a roommate.

"Growing up blind, my family never treated me differently," Wallace said. "Mostly, I've always felt confident."

But he hasn't always been so confident. "After graduation, Prudential Insurance was going to hire me to do website testing," he said. "I was a top candidate, by the way, so that was an honor." The catch: Wallace would have to move to a new city and live on his own.

"I turned it down," Wallace said. "It was like, 'Dude, I'm not ready to do that.' Something had to change."

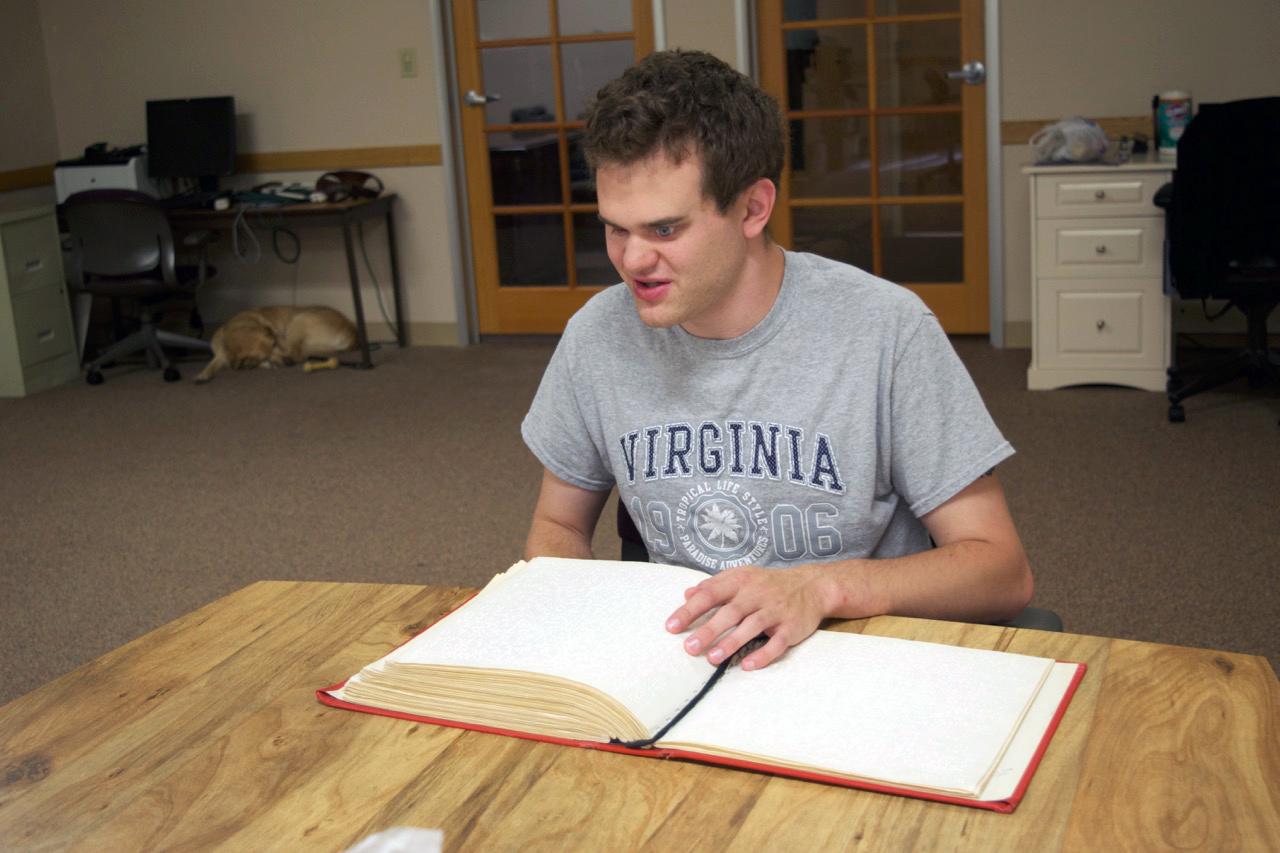

Wallace reading Braille at the Colorado Center for the Blind (CCB) in Littleton, Colorado.

That change came in the form of in-depth independence training at the Colorado Center for the Blind (CCB) in Littleton, Colorado. CCB offers classes focusing on travel, home management, Braille, technology and woodshop. In travel, students learn to navigate unfamiliar territories by identifying cardinal directions and analyzing complex street intersections. And then there's challenge recreation, a part of the travel course that's provided through the National Sports Center for the Disabled (NSCD) located in Denver and Winter Park. The course teaches CCB students how to rock climb, ski and complete an American Ninja Warrior-type obstacle course.

One of the largest outdoor therapeutic recreation and adaptive sports agencies in the world, the NSCD was founded in 1970 to provide ski lessons to children with amputations. Today, the organization serves about 3,200 people every year, including CCB students. With more than 40 paid staff, 1,200 trained volunteers and a 5-year-old big yellow therapy dog named Cinnamon, the NSCD provides a truly transformative experience.

"We work with organizations like the Colorado Center for the Blind, but we serve people with all types of disabilities," said Becky Zimmermann, president and CEO of NSCD. "Our participants may have a physical, cognitive or behavioral diagnosis. In many cases, working with the NSCD is one of the first times these folks have been able to participate in a sport."

Jarrod S., a National Sports Center for the Disabled (NSCD) participant, successfully completing a rock climbing challenge.

In the winter, NSCD participants enjoy alpine skiing, snowboarding, cross-country skiing, Nordic hut trips, snowshoeing and ski racing. In the summer, there are sports ability clinics and opportunities for rafting, kayaking, canoeing, therapeutic horseback riding, mountain biking, camping and rock climbing.

"I've had people tell me, 'I was ready to end my life, and then I found the NSCD,''' Zimmermann said. "The number one thing our activities help with is confidence and self-esteem. That's followed by the physical improvement."

"Challenge recreation forces you to get out of your comfort zone once a week," Wallace said. "You have to do each activity – rock climbing, skiing and the obstacle course – three times."

Rock climbing came easily to Wallace. Skiing didn't. His first time on the slopes was frustrating.

"By the third time, the guide told me that I was one of the better skiers she's ever seen," he said. "That was amazing to me. When I first started, I couldn't even stand on the skis without thinking I was going to break my ankles. I'm not saying I was one of the best, but in her opinion, I was. That was such a confidence builder."

Zimmermann says fundamentally, the NSCD is in the business of adaptation. It might be difficult to imagine someone with a disability mountain biking or skiing, but that's what's magical about NSCD. Skiing is a favorite among participants because it's the only place in life where gravity is their friend. "Anyone who is mobility impaired has freedom on the ski slope," Zimmermann said.

NSCD guides Kathy Keating, left, and Molly Niven teach Jayden and Ayla Mikes how to ski.

The NSCD has all kinds of gadgets designed by staff members to enable skiing. "You can't go to a sporting goods store and buy the stuff we need," Zimmermann said. All equipment is designed and tested in NSCD's state-of-the-art 2,100 square-foot adaptive equipment lab.

Every participant starts with an initial assessment. "We'll take a look at how someone walks – if they walk – how much upper body strength they have, and what their unique goals are," Zimmermann said. "We try to come up with an innovative solution for each individual."

Although there are a lot of adaptive sports organizations in Colorado, Zimmermann says NSCD is set apart by its goal-setting requirement. "That therapeutic goal is created by them, their parent or caregiver, and sometimes their physical therapist or occupational therapist," she said. "Sometimes it's a gentleman who had a stroke, and his goal is to use his left side more. But we also serve behavioral issues. Recently we had 10-year-old girl whose parents' goal for her was, at the end of five weeks, to have a friend."

The NSCD also has a Competition Center with a Paralympics club. Athletes travel from all over the world to train at an elite level. "Each winter Paralympics, there are probably 30 athletes that have trained with us," Zimmermann said. "In Vancouver in 2010, if the NSCD was a country, we would have won the third most medals in the Alpine events."

The organization only charges about 15 percent of the actual cost of their services. The other 85 percent comes from donors, fundraising events and foundations like the Union Pacific Foundation, which supported the NSCD with a $10,000 grant this year. "It takes a lot to be able to keep these programs going – it's very labor intensive," Zimmermann said.

Matt's Swagalicious Mini Meal

Wallace completes the mini meal challenge, a milestone in his home management course. To finish successfully, he had to prepare and serve a meal - including dessert - for 15 people.

Wallace graduates from the Colorado Center for the Blind Oct. 7. After that, he'll head back home to Philadelphia for his interview, and hopefully, with his new-found confidence and independence, feel comfortable accepting the job if it's offered.

"Skiing was a great learning experience," Wallace said. "Now, when I go back home, if a few buddies of mine say, 'Hey, we're going skiing tomorrow,' I'll at least know what they're up to. I might even tag along."