Railroading is and has been a male-dominated industry. While men have taken center stage on the railroad, that doesn’t mean women haven’t played an important role in railroad history.

“Women have always been part of railroading and the broader transportation industry,” said Debra Schrampfer, Chief Diversity Officer and AVP Workforce Resources for Union Pacific Railroad. “When the railroad moved west, it was no different than homesteading. While they weren’t awarded the same opportunities, women were there — tasked with physical labor, facing brutal elements and sometimes succumbing to the risks. Despite the gender limitations of the day, some spectacular women found a way to write their own history.”

The following stories of five female pioneers highlight the mark women have made on railroad history.

Mary Walton

The 2017 Union Pacific Museum exhibit "Move Over, Sir: Women Working on the Railroad."

Mary Walton was an early environmental pioneer. In 1879, she developed a way to deflect factory smokestack emissions using water tanks. This technology was later adapted for steam engines, which emitted large plumes of soot as they rode the rails.

As elevated trains became more prevalent in larger U.S. cities, Walton turned her attention to noise pollution. While useful for travel, these trains were excessively loud, creating a cacophonous environment for those who lived nearby. Walton lived in Manhattan, so she was familiar with the problem — and she set out to solve it.

Walton set up a model railroad track in her basement to test potential solutions. The winning idea involved cradling the rails in a box-like framework of wood, which was painted with tar, lined with cotton, and filled with sand. These materials absorbed the vibrations from the rails and in turn, also reduced the noise. In 1891 Walton patented her sound-dampening apparatus, the rights to which she later sold to New York City's Metropolitan Railroad. Walton’s invention both contributed to the railroad’s success and improved the quality of life for those who lived near elevated trains.

Learn more: https://lemelson.mit.edu/resources/mary-walton

Sarah Clark Kidder

At the age of 62, Sarah Clark Kidder became the first woman in the world to run a railroad. The year was 1901 and Kidder’s husband of 31 years, John Flint Kidder, had recently passed away. John was named president of the California-based Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railroad (NCNGRR) in 1884 and following his passing, Sarah’s inheritance put her in control of three-fourths of NCNGRR’s capital stock. But the role of president wasn’t simply handed to her: An overwhelming majority elected her to serve as the railroad’s new leader.

Despite having little business experience, Sarah Clark Kidder was wildly successful as president. When she assumed the role, the railroad was facing serious debt. Kidder set out to attract more freight and passengers to the railroad, positioning it to earn greater profits than ever before. By the end of 1903, just two years into her tenure, NCNGRR had its most profitable year ever.

Under Kidder’s leadership, the railroad paid off the $79,000 in funded debt and $184,122 interest on the debt; declared $117,000 in dividends on the company’s stock and added $180,000 to this surplus. When Kidder retired in 1913, NCNGRR was in the best financial shape it had ever been in or ever would be.

Avis Lobdell

Avis Lobdell not only worked for the railroad, but she also made it more comfortable for other women to ride the rails, too. In 1935, Union Pacific President William Jeffers wanted to provide a first-class experience for passengers who rode coach (as opposed to one of the railroad’s luxury Streamliners). So, he asked Lobdell to ride Union Pacific’s Challenger train, which was intended to offer outstanding service at Depression-era prices, and ask passengers how Union Pacific could improve their train riding experience.

Lobdell talked with passengers as she rode the Challenger along its entire route from Chicago to Los Angeles. Through her research Lobdell discovered that women, who comprised more than half of coach passengers, had a number pain points while traveling by train. In particular, women noted the inconveniences they encountered while traveling alone or with only their children.

While many failed to take Lobdell’s research seriously, Jeffers’ saw its value. He created the Women’s Travel Department and made Lobdell the head. There she was responsible for hiring nurses to assist single women, mothers traveling without help, and the elderly and infirm. The railroad also established women-only train cars, which the nurses/stewardesses were placed in charge of. Even the passenger conductor had to get permission before he could enter.

The Challenger became one of the most successful trains in Union Pacific history; it’s no doubt Lobdell’s efforts were a great part of that success.

Learn more: https://www.uprrmuseum.org/uprrm/exhibits/traveling/women-railroad/index.htm

Bonnie Leake

Bonnie Leake

In 1974, Bonnie Leake shattered the glass ceiling when she became the first woman accepted by Union Pacific Railroad to train as a locomotive engineer.

Leake had joined the railroad in 1966 as an office clerk and later served as a crew dispatcher. As a single mother, she had her sights set higher, though — and they landed squarely on becoming a locomotive engineer. “I saw how much money the men made, and I knew I could handle the job,” Leake said in a 2017 Inside Track article. In 1974, after training for six months and meeting the physical requirements (as well as tolerating intense scrutiny), Leake accomplished her dream of becoming an engineer, running trains from Las Vegas to Milford, Utah, and Yermo, California. She accomplished this all before the age of 30.

When she retired in 2007, Leake had served on the railroad for nearly 40 years. “If you think of yourself as equal, you’ll eventually be treated that way,” she said.

In January 2021 Leake passed away at the age of 76.

Learn more: https://www.progressiverailroading.com/people/article/UPs-Bonnie-Leake-Hitting-The-Brakes--13377

Edwina Justus

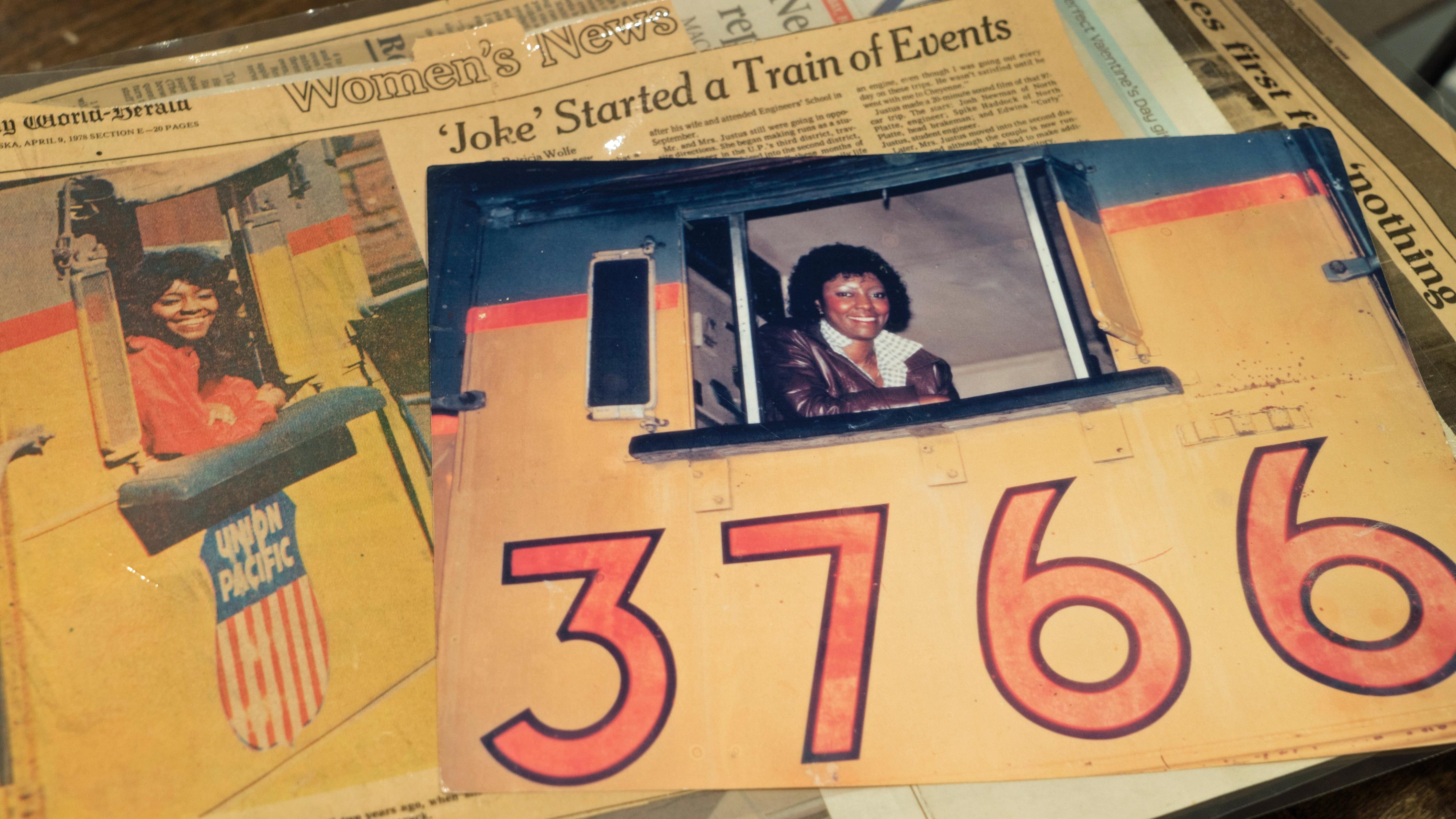

Edwina "Curly" Justus

Edwina “Curlie” Justus was the first Black woman locomotive engineer for Union Pacific Railroad. But her groundbreaking railroad career didn’t begin there — and that wasn’t the only noteworthy “first” in her life.

Growing up in Omaha, Nebraska, Justus was the first Black student enrolled at Brown Park Elementary School. She graduated from high school in 1960 and worked as a wireman at Western Electric for the next eight years. In 1969, she enrolled at the University of Nebraska, where she studied to become a social worker.

While at Western Electric she applied for a position at Union Pacific, but her application was denied due to her gender. That didn’t stop Justus from pursuing a career at the railroad. In 1972, a friend told her Union Pacific was accepting applications for open clerical positions. This time, Justus was not turned away. In 1973 she left the University to take a job as a Traction Motor Clerk. At the time, she was one of just five Black women working for the company.

In 1976 at the age of 34, Justus became the first Black female engineer. This role took her and her husband to North Platte, Nebraska. She spent the next 22 years hauling items such as livestock, automobiles and airplane wings to Cheyenne, Wyoming, and Denver, Colorado, always appreciating the landscape as she went. “When I was in school, I liked to daydream,” Justus recalled in 2017. “A teacher told me I’d never be successful staring out the window; she was wrong.”

After retiring in 1998, Justus moved back to Omaha with her husband, who also retired as an engineer.

In 2017, Justus met her first fellow female engineer, Bonnie Leake, at an exhibit at Union Pacific’s Museum in Council Bluffs, Iowa. The exhibit, titled “Move Over, Sir: Women Working on the Railroad,” recounted the experiences and accomplishments of both Justus and Leake, as well as other women in the industry. Justus’ also recounts her career in her book “Union Pacific Engineer: An Autobiography of UP's First Black Woman Locomotive Engineer,” which she released in December 2021.

Documenting History, Increasing Representation

Leake and Justus meet for the first time at the 2017 Union Pacific Museum exhibit opening

Looking back at the contributions of women helps us recognize their achievements and ensure they keep their hard-earned place in railroad history. But women’s history can also be a catalyst for creating a more inclusive future.

“We are so fortunate at Union Pacific that several of our amazing women, who accomplished ‘firsts,’ shared with us their stories,” said Debbie. “Documenting these narratives are critical to understanding women’s evolving role in the workplace as well as inspiring future generations.”

The railroad may be a male-dominated industry, but Union Pacific is working to change that. We have set the goal of doubling the number of women in our workforce by 2030 and are committed to increasing the representation of both women and people of color in our industry. Visit our Diversity & Inclusion page to learn more about our mission, vision and strategy.

Related Articles

- A History of Black Leaders in Transportation

- The Impact of Black Inventors on the Railroad

- From Steam to Green: The Evolution of the Locomotive

- Surprising Railroad Inventions: U.S. Time Zones

- Surprising Railroad Inventions: The Ski Lift

- A Historic Hemp Shipment

- Rail: An Environmentally Responsible Way to Ship