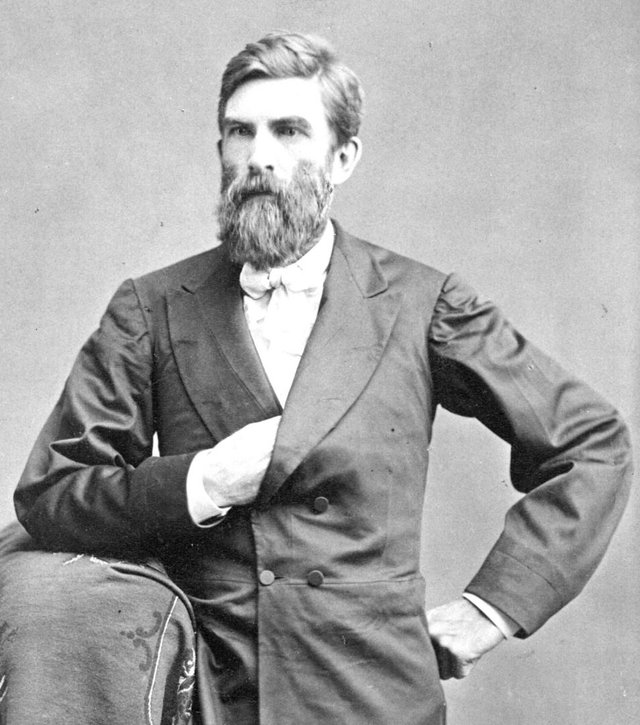

The construction of the UP was led by Thomas C. Durant, vice president and general manager of Union Pacific, president of the Credit Mobilier, and a self-serving financial strategist. By the end of 1865, the UP had spent more than $500,000 and laid only 40 miles of track, or as one newspaper said, "two streaks of rust across the Nebraska prairie." To salvage the fortunes of construction, Durant offered the job of chief engineer to a young union general and civil engineer, Grenville Dodge. Dodge wrote, "It fell to my lot to be chief of this party."

During the Civil War, Dodge had built or rebuilt railroads so fast that they used to say of him, "We don't know where he is, but we can tell where he has been." Dodge knew Durant well, for they had worked together building railroads in Iowa. In his letter of acceptance to Durant he wrote, "I will agree to work for the UP, but I must have absolute control in the field." In a letter to his brother, Dodge wrote, " . . . the UP would pay me well, but I'm afraid I might have trouble with Durant." This statement would prove to be prophetic.

Finding wood for ties on Nebraska's nearly treeless prairie was one of the UP's worst problems. Any tree of sufficient size, hard wood or soft, was used. As the road extended westward, canyons full of cedar trees near North Platte fell to the ax, and workers crafted hewn ties in the mountain forests of Wyoming. Despite the constraints imposed by transportation needs, and the sheer amount of handwork to be done, progress was made. Dodge wrote, "To supply one mile of track with material and supplies required about forty cars, as on the plains everything – rails, ties, bridging, fastenings, all railway supplies, fuel for locomotives and trains, and supplies for men and animals on the entire work – had to be transported from the Missouri River. Therefore, as we moved westward, every hundred miles added vastly to our transportation. Yet the work was so systematically planned and executed that I do not remember an instant in all the construction of the line of the work being delayed a single week for want of material." This feat was accomplished by Samuel B. Reed, chief of construction and formerly a locating engineer. Reed's job was to keep the supplies moving and oversee construction in the field.

Building east from California, the CP bridged ravines with trestles. Ridges were carved and blasted through. There was a chronic labor shortage, as most able-bodied men preferred trying to strike it rich in the gold mines. However, a large Chinese work force, numbering 10,000 or more, originally drawn to California by the gold rush, was eventually drafted into the effort. By the second year of work on the CP's construction, nine out of ten of the workers were Chinese.

Building west from Omaha, there were problems of a different nature. To construct a road, the Union Pacific had to cross land occupied by American Indians. From the Native Americans' perspective, it was imperative to protect their families and homeland against the imminent invasion of a flood of immigrants. The Indians repeatedly attacked without warning, and the UP acted as its own army. Dodge himself was obsessed with the problem. He wrote, "In 1866 the country was systematically occupied ... day and night, summer and winter, explorations were pushed forward through dangers and hardships that very few at this day appreciate, for every mile had to be run within range of the musket, as there was not a moment's security. In making the surveys, numbers of our men, some of them the ablest and most promising, were killed; and during the construction our stock was run off by the hundred, I might say, by the thousand." He wrote to General Sherman, commander of the Military Division of the West, "We've got to clean the Indian out, or give up. The government may take its choice."

There was no mystery about how to do the job. The solution was practically larger than life. Sherman knew that the bison was the source of food, clothing and shelter for the plains tribes. The railroad, by bisecting the great herds of bison, provided a source of transportation for hunters, thus speeding up their elimination. Eradicating much of the bison population provided an earlier end to the hostilities than otherwise might have been the case.

Westward construction continued. The workers, many of them Irish immigrants or veterans of the Civil War, were paid the average of a dollar a day. These were the pick and shovel men, the teamsters, blacksmiths, masons, carpenters, mechanics and track layers.

The track laying crew was managed by the Casement brothers, Dan and Jack. Tough as nails and given to dressing like a Cossack, Jack Casement worked his men hard. The crews lived in 20 cars, including dormitories and an arsenal car containing a thousand loaded rifles.

A newspaper reporter present at the construction in 1866 wrote, "The track laying on the Union Pacific was a science. We, pundits of the far East, stood upon that embankment, only about a thousand miles this side of sunset, and backed westward before that hurrying corps of sturdy operators with a mingled feeling of amusement, curiosity and profound respect. On they came. A light car, drawn by a single horse, gallops up to the front with its load of rails. Two men seize the end of a rail and start forward, the rest of the gang taking hold by twos, until it is clear of the car. They come forward at a run. At the word of command the rail is dropped in its place, right side up with care, while the same process goes on at the other side of the car. Less than thirty seconds to a rail, and so four rails go down to the minute. The moment the car is empty it is tipped over on the side of the track to let the next loaded car pass it, and then it is tipped back again, and it is a sight to see it go flying back for another load, propelled by a horse at full gallop at the end of sixty or eighty feet of rope. Close behind the first gang come the gaugers, spikers and bolters, and a lively time they make of it. It is a grand 'Anvil Chorus' that those sturdy sledges are playing across the plains. It is in triple time, three strokes to the spike. . .ten spikes to a rail, four hundred rails to a mile, eighteen hundred miles to San Francisco. Twenty-one million times are those sledges to be swung ... before the great work of modern America is complete."

Before long, the UP was laying a mile or more a day. Dodge wrote, "They could lay from one to three miles of track per day as they had material, and one day laid eight-and-a-half miles." The crews worked seven days a week, 12 to 16 hours a day, with few weekends to themselves. What little free time they had they spent in drinking, carousing and fighting. In Cheyenne, murders outnumbered accidental deaths four to one. Taking the law into his own hands, Jack Casement undertook the discipline of the most incorrigible railroad workers. In a report to Dodge, Casement wrote that " few of the sinners had survived the encounter."

Pushing west through Wyoming was exhausting and treacherous. A 650-foot bridge spanning Dale Creek had to be constructed. The longest trestle on the line, it rose 150 feet up from the bottom of the canyon, swayed in the wind and was terrifying to cross.

Weather was a constant opponent as well. West of Cheyenne, one encounters some of the most inclement weather in the country. Dodge wrote, "Central Wyoming was desolate, dreary, not susceptible to cultivation and only portions of it fit for grazing." Jack Casement wrote to his wife, "This is an awful place; alkali dust knee-deep. We haul all our water 50 miles and we're losing a great many mules, six nice fat ones died in less than an hour today." In winter, the cold was beyond belief. In warmer months, it was unimaginably hot. In the desert, the ambient temperature was around 110 degrees, while the temperature inside the engine cab topped out at 150 to 160 degrees.

Out west, the CP was having troubles of its own, blocked by the massive, solid granite ridges of the Sierra Nevada. The goal was to make a tunnel, so holes had to be drilled in the rock face for explosives. It took three eight-hour shifts to drill a twelve-inch hole, and the steel drills had to be given new edges by blacksmiths every two hours. Black blasting powder was then tamped into the holes, a very dangerous occupation considering the fact that the least spark could ignite the powder and blow a crew to bits. Because the work was proceeding so slowly, a very volatile explosive, nitroglycerin, was brought to the scene. Although it doubled progress, the increase in speed came with a terrible price, and it soon proved to be too dangerous. Crews returned to using black powder and after a year, the 1,600-foot tunnel was complete.

Winter weather was the CP's greatest, most underestimated problem. During the winter of 1866, it took nearly half the CP work force of 9,000 men just to keep the track shoveled. Eventually crews constructed enclosed wooden snow sheds around the track, enabling them to continue making progress. Still, the crews had to contend with frostbite, pneumonia, inadequate shelter and avalanches of snow.

Now the focus was the Salt Lake Valley. Whoever reached Ogden first could establish a depot and capture the lucrative Salt Lake business. The amount of money at stake prompted a frenzy to be first. Each road graded a line far beyond where the tracks would finally meet, with the hope that the government would approve one line over the other. True to form, however, the government compromised, selecting a meeting site halfway between the ends of the graded lines. As Dodge notes in "How We Built the Union Pacific," this site was "at the summit of Promontory Point;" words which perhaps caused the confusion in names that continues to this day. In his telegram to Oliver Ames on May 8, 1869, Dodge says "You can make affidavit of completion of road to Promontory Summit." This is where the rails met and the ceremony took place on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit. Promontory Point is a bit of land that extends into the Great Salt Lake. The meeting site at the summit of Promontory Point permitted completion of the railroad without having to build across any portion of the Great Salt Lake, a feat that may have been either too difficult technologically or just too time consuming for the parties involved.

In the last weeks of construction there were additional dramas. Dodge wrote, "The Central Pacific had made wonderful progress coming east, and we abandoned the work from Promontory to Humboldt Wells, bending all our efforts to meet them at Promontory. Between Ogden and Promontory each company graded a line, running side by side, and in some places one line was right above the other. The laborers upon the Central Pacific were Chinamen, while ours were Irishmen, and there was much ill feeling between them. Our Irishman were in the habit of firing their blasts in the cuts without giving warning to the Chinamen on the Central Pacific working right above them. From this cause several Chinamen were severely hurt. Complaint was made to me by the Central Pacific people, and I endeavored to have the contractors bring all hostilities to a close, but for some reason or other, they failed to do so. One day the Chinamen, appreciating the situation, put in what is called a "grave" on their work, and when the Irishmen right under them were all at work let go their blast and buried several of our men. This brought about a truce at once. From that time the Irish laborers showed due respect for the Chinamen, and there was no further trouble."

Finally, the unification of east and west was at hand. Gleaming trains carrying a fleet of officials set off from Sacramento and Omaha. The UP, plagued by weather, flash flooding in Weber Canyon and a revolt by unpaid railroad workers at Piedmont (featuring the kidnapping of Durant), were late. The weather subsided, tracks were relaid and the New York Board of Directors wired $500,000 to subcontractors to make the payroll and free Durant. It is possible that Durant had planned everything but the weather in order to collect a kickback from the subcontractors; 10 percent of the $500,000.

The skies cleared over Promontory on May 10, 1869. The occasion was commemorated with the ceremonial joining of the last rails and the driving of the last, now-famous, golden spike. Its symbolic power riveted the attention of a nation. Western Union offered live coverage direct from the scene to waiting multitudes, and reporters and photographers immortalized the occasion which culminated four years of backbreaking labor.

Durant, representing the UP, was to drive a silver spike, and Stanford of the CP, a golden one. Durant tapped his into a pre-drilled hole. When Stanford went to drive his, he missed. The telegrapher signaled "Done." and a legend was born. The next day presented a strange anticlimax, as all hurried back to distant cities on the new lines, leaving Promontory an almost deserted whistle-stop on the new Transcontinental Road.

It was now possible to leave San Francisco and arrive in New York in 10 days. The railroad had opened the heart of the continent, changing it forever. Dodge wrote, "When you look back to the beginning at the Missouri River, with no railway communication from the east and 500 miles of the country in advance without timber, fuel or any material whatever from which to build or maintain a road, except the sand for the bare roadbed itself; with everything to be created, with labor scarce and high, you can all look back upon the work with satisfaction and ask, 'under such circumstances could we have done more or better?' "

David McCulloch writes, "In the same year the road was completed, 1869, another monumental epic engineering feat was completed; the Suez Canal. Suddenly the world was getting smaller, an idea that inspired Jules Verne to write 'Around the World in Eighty Days.' "

"In the half-century following 1880, the railroad industry reshaped the American landscape and reoriented American thinking. The luxury passenger express hurtling past smalltown depots, the slow freight trains chugging through industrial zones, the commuter locals shuttling between suburban stations and urban terminals heralded the forces of modernization and touched millions with the romance of the rails. The allure of the railroad and the metropolitan corridor that evolved around it lasted until the ascendancy of the automobile, when the railroad suddenly vanished from national attention."

John R. Stillgoe, author of "Metropolitan Corridor"