After construction of the transcontinental railroad was completed, the settlement of the vast interior of the West moved full steam ahead. Land was cheap, railroad towns boomed, and industry flourished. Early on, acreage along the UP was perceived as better suited to grazing than farming, so it was natural that UP became the major carrier of grassfed beef to Chicago markets. Other markets, such as that of coal, developed along similar lines.

The Panic of 1873 triggered one of the fiercest industrial rate wars in the history of railroading. During this period of decline, the oft-maligned and controversial Jay Gould assumed the presidency of the UP. Gould ultimately kept the UP afloat. He also practiced pitting one railroad against another, forcing the UP into consolidations, most famously the merger with the Kansas Pacific. Although consolidation was blamed for the UP's financial difficulties, it actually may have worked to the company's advantage. For better or worse, Jay Gould may have been ahead of his time. Buying rival lines as an act of self-defense would become standard practice among railroads by the 1880s.

In 1893, the Union Pacific and every other railroad in the country paid the price for overexpanding, overproducing, and overspeculating. They fell heavily into debt. The Panic of 1893 was also the result of inflation, floating debts, overcapitalization, drought, and severe competition. All sectors of the economy were affected as banks and brokerage houses failed, and even the New York Stock Exchange closed for an unprecedented ten days. As the eastern business world collapsed, western railroads failed. Loans were called, capital was impossible to obtain, and government and company securities fell. Construction came to a halt and many lines went into receivership.

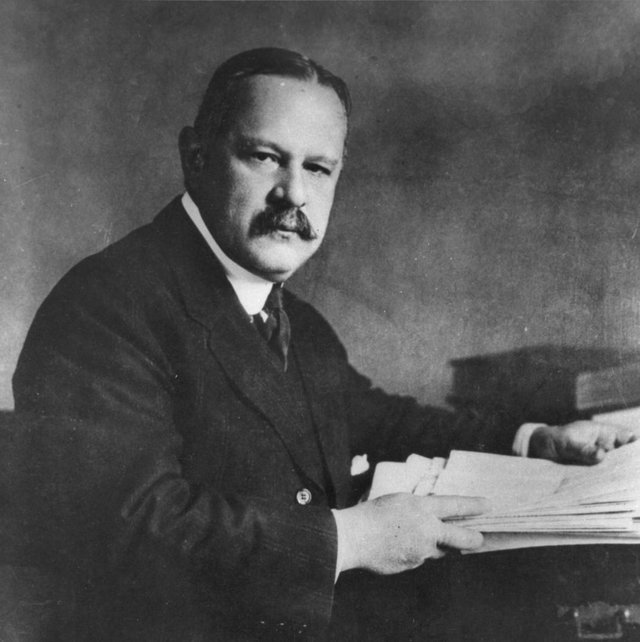

Like many others, the Union Pacific, unable to meet its expenses, was placed in the hands of three receivers. The property was sold at foreclosure under order of a federal court on November 1, 1897. The buyers, a small group of investors including E.H. Harriman, paid $110 million for the line from Omaha to Ogden. Title and property were conveyed to the present Union Pacific Railroad Company. Harriman spent the next decade reorganizing the company and reacquiring other major portions of the pre-1893 Union Pacific . He rehabilitated company properties by spending millions of dollars for modern locomotives, freight and passenger cars; eliminating curves; reducing grades; replacing wooden bridges with steel or masonry; constructing cutoffs; reducing mileage; improving water supply; enlarging operations yards; installing heavier rail; and double tracking by the hundreds of miles. He returned the railroad to prosperity.

Just before the turn of the century, the UP and every other railroad in the country got their first taste of rate regulation. The Interstate Commerce Commission, signed into law in 1887 to establish "just and reasonable maximum rates," had a devastating impact on American railroad companies. Railroad scholar John Stilgoe writes that, however well meant, rate setting by the I.C.C. played havoc with railroads and the public by assuaging special interest groups in the name of protecting citizens and the national economy. Government regulators used public dislike of railroads during the late 19th century to cripple a 20th century industry, as well as the industries dependent on it. Railroad management, bludgeoned by Government restrictions, low earnings and new competition, was about to begin a long, painful rejuvenation.

The next decades were characterized by further regulation, oversight, and war. Throughout World War I, Union Pacific moved Allied supplies and personnel to eastern seaboards for shipment across the Atlantic. In addition, in response to traffic problems and a variety of war emergencies, the chief executives of several major railroad companies united to form one national rail network under the direction of the Railroad's War Board. In 1917, President Woodrow Wilson, in an effort to bring the railroads under further government control, created the United States Railroad Administration, an agency uniting all railroad companies into one national rail network, as the country's participation in WWI increased. At the war's end, Congress returned the railroads to private ownership.

The years between the wars were characterized chiefly by competition. With the advent of the Model T, the American public suddenly had the option of conveying themselves around the country. Travel by car, tour bus, and soon, by plane, heralded the decline of rail passenger travel, at least for the moment. The railroad industry was also threatened with the emerging economical trucking industry, which promised to take a bite out of the freight business.

These years of decline however, led to an all out push for increased efficiency. Locomotives and equipment were improved, the loading and unloading of freight cars became a science, and mileage was increased per freight car. This was also the age of luxury passenger travel. In 1934, the Union Pacific introduced the Streamliner "City of Salina," an ultramodern, high-speed diesel powered train set which included a coach and a combination coach-buffet. New sleeping cars came with a range of accommodations, including a newly designed roomette, in addition to sections, bedrooms, compartments and drawing rooms. Richly appointed and air-conditioned, dining cars used fine china, silver and linen. Never had the American public been afforded such opulence in passenger rail travel, a standard which would last another 40 years.

During World War II, the UP played an essential role in the transport of supplies and personnel, spending around $414 million on the effort. Unlike WWI, WWII became a "two front" conflict, necessitating the flow of rail traffic in both directions. This eliminated the congestion of cars at port which had so plagued the industry during World War I. One of the Union Pacific's most visible contributions to the war effort was its maintenance of servicemen's canteens and USOs at stops like Omaha, North Platte, Pocatello and Boise. In North Platte alone, every day from 1942 to 1945, as many as 10,000 servicemen and women came through on their way to war. The people from surrounding towns met every train, fed every soldier, and no one was ever presented with a bill. Though the UP depot at North Platte is now gone, the memory of the canteen will not be forgotten. It lives on in the memories of the hundreds of volunteers and soldiers who stopped there.

After the war, the UP experienced a new decline in passenger service. Legions of servicemen came home, bought cars and began vacationing in them on the nation's improved roadways. Meanwhile, the government began a major campaign to fund the highway and interstate system to accommodate these new commuter travelers. The railroads' response was to increase efficiency still more. It was a slow climb back to quality service, capital reinvestment and profitability, but American railroads staged an impressive comeback.

Today, the Union Pacific is one of the largest and fastest growing transportation companies in the United States. It is also the oldest railroad company in continuous operation under its original name west of the Mississippi River. Every day of the week, several hundred trains travel through UP territory, aided by state-of-the-art telecommunications services, advanced fiber optics, and the Harriman Center's computerized dispatching capabilities.